Reading Between the Posts : Evidence from Facebook Expat Groups

We analyzed 23,000 Facebook posts using text-as-data methods to uncover how immigrants in France share needs, navigate crises, and find community online.

Imagine you’ve just arrived in a new country, for studies, for work, or simply taking a shot at life. You don’t speak the language fluently. The landlord you had a ‘solid’ agreement with suddenly backs out. To rent another place, you need a bank account, but to open it, you need proof of housing. You call the social security office, but they speak too fast. You’re lost in administrative translation.

So who do you turn to? For many immigrants, the answer is: strangers in Facebook groups.

From visa questions and housing leads to everyday discussions, immigrant support communities online, or ‘expat groups’1, have become an essential part of how people navigate life abroad. These groups are practical, decentralized spaces, often organized by nationality (“Colombians in Lille,” “Americans in Lyon,” “British in Paris”2), covering a wide spectrum of topics, tones, and intentions. For some, it’s about making ends meet; for others, it’s about building a life that feels truly their own.

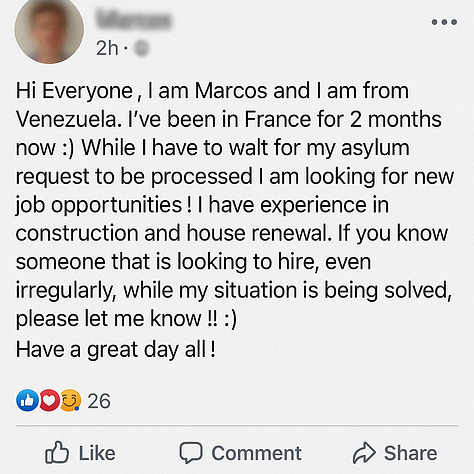

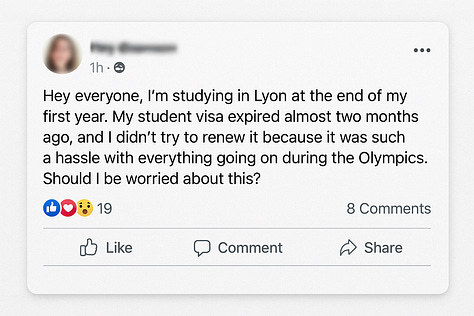

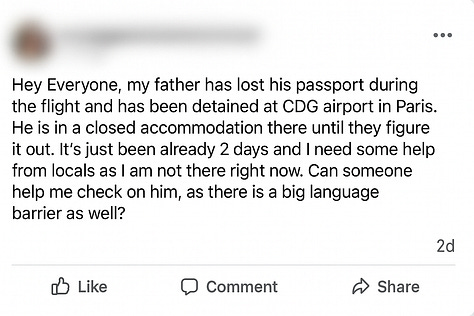

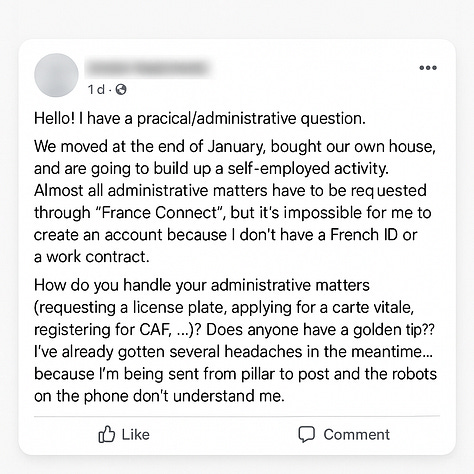

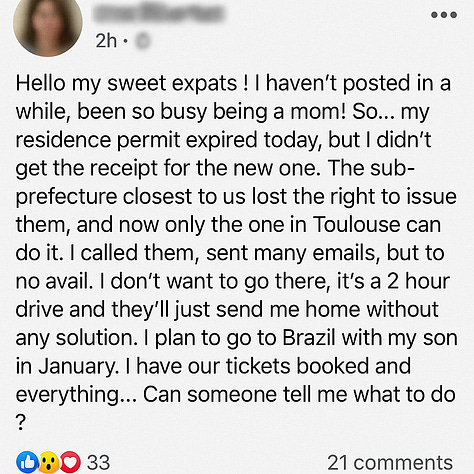

Below are a few examples3 that illustrate the wide spectrum of tones and themes found in these groups.

Unlike most studies based on surveys or administrative records, this project draws on bottom-up, unfiltered narratives from immigrants themselves. Our aim is to use these digital traces to understand what drives people to seek help in online support groups, and how they articulate their needs.

While the dataset is skewed toward certain nationalities, age groups, and the kinds of people who use Facebook (and thus not representative of anyone’s full immigrant story, what is to say of France’s full 7.3 million immigrant population) it offers something most surveys cannot: a grassroots perspective on integration struggles in real time.

We analyze over 23,000 posts4, covering around 20 different nationalities, collected from over 84 expat groups. With the help of large language models5 (LLMs), in addition to traditional natural language processing techniques, we identified surface-level patterns (such as country-specific vocabulary), extracted self-declared traits (such as the poster’s gender or housing budget), and detected deeper narrative signals including urgency, family references, or expressions of religious identity. We then relate these features to country-level traits (such as GDP per capita or EU membership) to explore broader differences in how the various expat communities describe and approach life in France.

1. Language as a Lens: Country-Specific Vocabulary

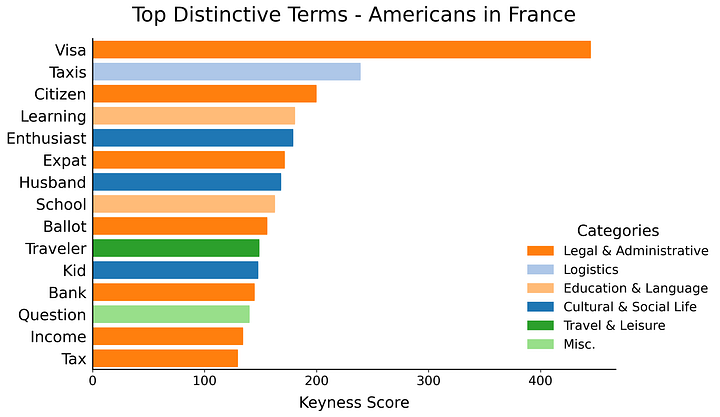

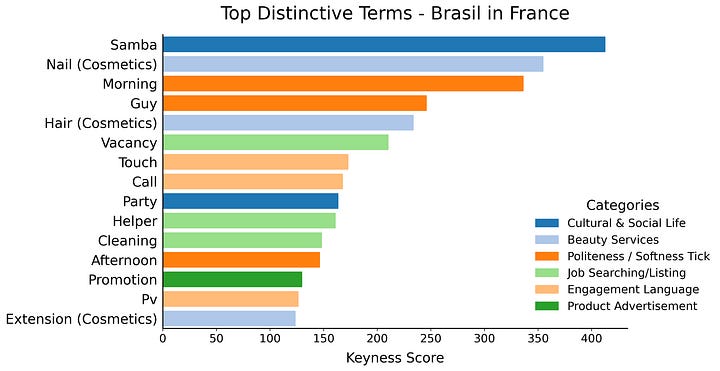

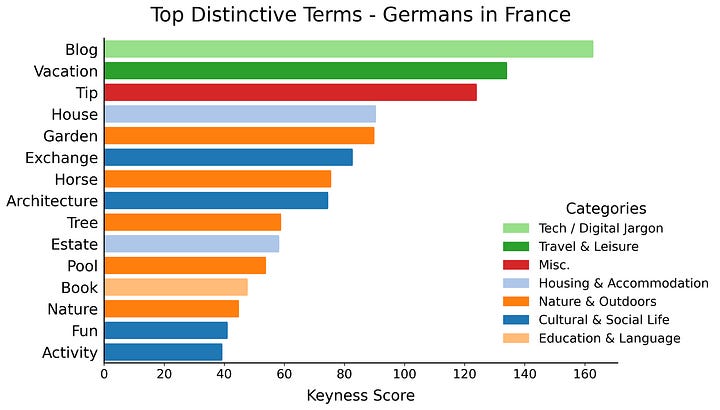

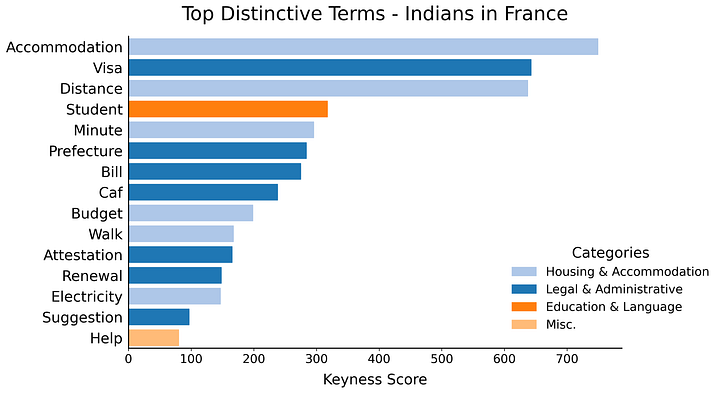

We begin by asking a simple question: do different national groups use distinctive language when posting in Facebook expat communities? To investigate, we compute keyness6 scores: a statistical measure that highlights words that appear unusually often in one group’s posts compared to all others. So, which words and terms stand out as especially predictive of each group?

The contrasts are revealing. Brazilian users in France frequently use terms related to job-seeking and informal services, such as cleaning, vacancy, or hair/nail extensions, proportionally much more than others. Americans, by contrast, are more distinguishable through vocabulary tied to planning and administrative life: visa procedures, school enrollment, taxes, income transfer. Indian posts stand out for housing-related terms, whether referring to budgets, locations, or state benefits. Finally, German users7 use more language related to nature and outdoor activities.

While these vocabulary patterns don’t fully represent what each group is discussing, they offer early clues about the practical needs and priorities that drive people to post.

2. Extracting Structured Information with LLMs

Next, we turn to structured information extraction. In this step, we identify posts where users are searching for or offering accommodation and explicitly mention a rental budget. In practice, housing is one of the first and biggest expenses that ties newcomers into the local economy and society. It determines which neighborhoods they can live in, the quality, size, and stability of their living situation, and more. In this sense, declared budgets could provide a simple but useful lens on purchasing power and economic integration across groups.

For each post, we prompt the model to extract the budget amount and currency, if stated. To make the results comparable, we limit the sample to housing posts in the Paris region. We also normalize values across posts by adjusting for currency (euros, Danish kroner, etc.) and for time units (monthly vs. weekly rent8). This gives us a standardized observation set of declared housing budgets across different nationalities.

A clear pattern emerges: migrants from higher-GDP countries tend to report significantly higher expected rental budgets. While not surprising, this supports the idea that the variation between groups reflects meaningful socioeconomic differences.

Based on reading a sample of the housing posts, we propose a rough interpretation: the lower end of the budgets, reported by Latin Americans9 and Indians, mostly reflects groups composed of young immigrants, such as students or lower-wage workers. The middle range, from Ukrainians to Italians, is more mixed, including both lower-wage workers and families relocating for economic or even geopolitical reasons. In contrast, the higher end of the budget scale tends to include housing posts from families and more established households with higher-income jobs.

This result also goes to show that GDP per capita can serve as a convenient proxy to help distinguish between nationality groups. Naturally, it’s not the wealth of the country of origin per se that determines these declared budgets. But this metric does a pretty good job of showing how nationality, at the aggregate level, is associated with the selection of migrants from different socioeconomic backgrounds, which is ultimately what drives what they expect (or can afford) to pay.

3. Extracting Narrative Signals and Classifying Integration Challenges

An online support group is, above all, a place where wisdom and information are either requested from the community or offered back to it. While some posts are purely transactional, such as advertising a cosmetic service or selling second hand products, many others reflect deeper personal experiences.

To focus on these, we prompt the LLM to keep posts where users are:

Seeking advice or guidance.

Sharing personal stories to request moral support.

Voicing opinions or reflections to spark group discussion.

We then classify these posts into different dimensions of integration10, such as housing instability, social belonging, or labor market insecurity. In parallel, we extract a set of narrative signals, including:

Urgency: Does the post convey a sense of desperation or use time-sensitive language?

Family references: Does the situation involve a spouse, children, or relatives?

Religious identity: Does the user employ religious expressions (“God bless,” “inshallah”) or explicitly identify with a given faith?

Each post is also matched with characteristics of the expat group it comes from, such as the GDP per capita of the country of origin and whether it is an EU member11. Where possible, we also infer the gender of the poster, based on first names.

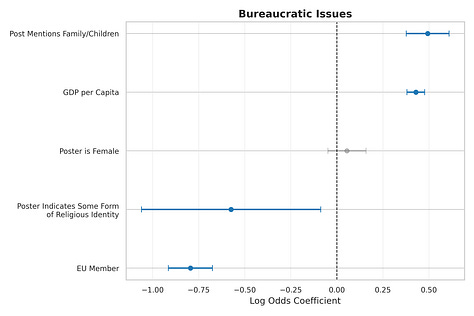

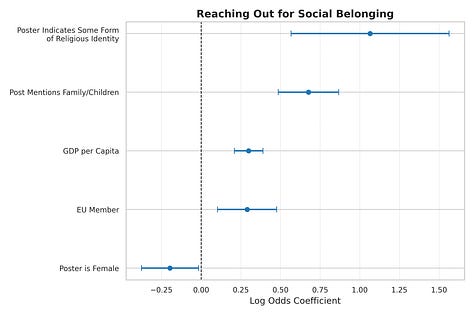

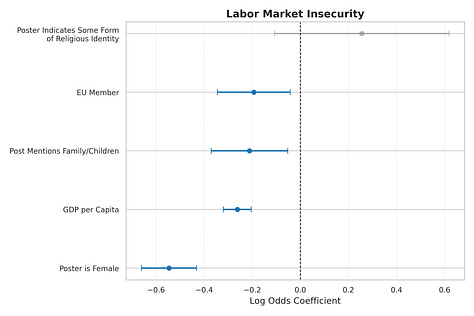

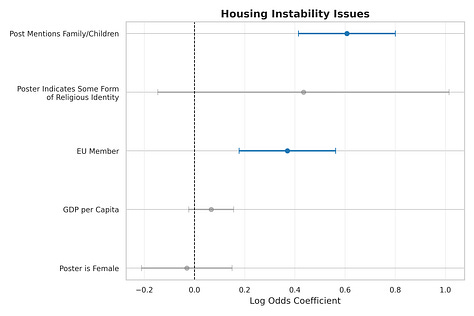

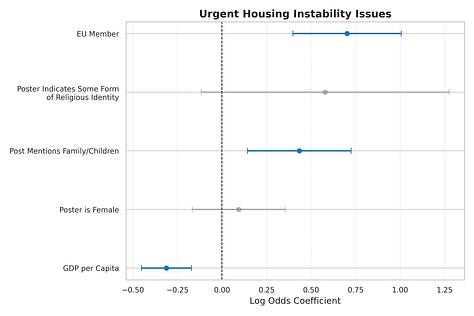

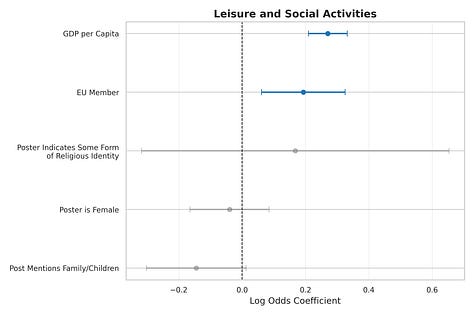

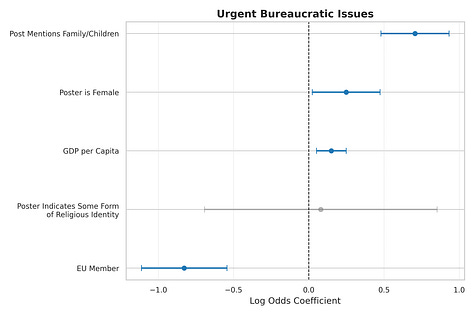

With these structured features, we run a series of logistic regressions to explore which communities are more likely to post about which types of problems. The plots below show the log-odds coefficients for some of our regressions : a positive value means the characteristic makes a post more likely to fall into that category, while a negative value means it makes it less likely. Coefficients shown in gray are not statistically significant, meaning they are not reliable predictors for that specific category.

We find that migrants from non-EU, and lower-income countries more broadly, are significantly more likely to use support groups to address labor market insecurity, highlighting persistent challenges around employment and economic precarity. But this doesn’t mean migrants from higher-income or EU member states are silent or free from integration struggles. Instead, they more often post about social belonging12, housing instability, or bureaucratic confusion.

These aren’t necessarily signs of greater hardship (though sometimes they can be) but rather of different frictions. Not the urgent problems that appear right after arrival or at the end of the month, but the ones that emerge as people start seeking deeper legal stability and belonging. The right job, the right neighborhood, the right social circle.

Take housing, for example. Posts from expat groups tied to higher-GDP countries and EU member states are more likely to raise housing-related issues. Given the higher budgets observed earlier, this may seem counterintuitive. But when we isolate urgent housing needs, the pattern flips: migrants from lower-income countries are significantly more represented.

In other words, while housing concerns are common across all groups, tone and urgency tend to vary between expat communities from lower-GDP and higher-GDP countries. On one side, posts reflect immediate necessity : a scramble for any place to stay. On the other, they reveal a search not just for shelter, but for the right place to settle.

Another similar insight comes from the social belonging category. Here, we see the only case where expressing religious identity is positively associated with posting. Typically, expats might reach out to find others to spend religious holidays with or to socially network within expat religious communities. This highlights how faith can also be leveraged in these groups to find, or build, a particular kind of social circle.

Finally, gender shows an interesting pattern as well. While it isn’t always a strong predictor of post topics, urgent bureaucratic problems seem to be disproportionately raised by female posters. This may reflect gendered responsibilities in navigating institutions, particularly for family and healthcare matters.

Taken together, these results highlight an important nuance in how migrant communities use support groups: not just the type of challenges they face, but the stage they are in their integration journey. Even migrants with more stable legal status or stronger economic footing continue to seek support and wisdom from fellow expats. What may begin as a scramble for basic living conditions can gradually turn into a search for stability and belonging.

Conclusion

Expat groups show that online support is leveraged not only at arrival or during moments of crisis, but throughout an entire migration journey. Ultimately, these communities are not just spaces for functional exchange, but places where strangers help each other navigate life in a new society. Thanks to LLMs we can now infer context, classify subtle signals, and handle informal or messy language across thousands of posts at once, faster and cheaper than ever before. Even through a basic lens like the one used here, meaningful patterns emerge. And there’s still much more to uncover.

The words expat and immigrant carry different implications and cultural baggage. In general, an expat is someone residing abroad, often for a fixed amount of time, whereas an immigrant usually relocates with the aim of settling permanently. In practice, the lines can be blurry between the two. Some nationality groups online tend to describe themselves more often as expats, while others more readily use the word immigrant. Although unpacking this nuance is beyond the scope of this article, we use the term expat group throughout for consistency.

Group names are indicative but fictitious, used solely to illustrate the types of communities studied without exposing any specific group. All analyses focus on narrative patterns and group-level dynamics only. Findings are presented in aggregate to preserve user anonymity and respect the context in which the posts were shared.

The posts analyzed were collected from Facebook groups where migrants share their experiences. Users may post under their public name or anonymously. All post examples are faithfully translated, but paraphrased. Any specific information that could potentially be used to trace the original poster (including names, nationalities, dates, and locations) has been modified. The ‘screenshots’ themselves are AI-generated images using the paraphrased translations, with fictitious names.

The insights presented here are derived from posts by the following nationality groups: Americans, Argentinians, Australians, Brazilians, British, Czechs and Slovaks, Danes, Dutch, Germans, Greeks, Hungarians, Indians, Israelis, Italians, Latin Americans, Norwegians, Pakistanis, Poles, Russians, Spaniards, Swedes, Tunisians, Ukrainians. Naturally, coverage depends on the collection period and the number of active expat communities available for each nationality. In practice, the largest nationality represented in the dataset has just over 4,000 posts, while the smallest still has around 300. On average, each group contributes about 1,500 posts.

Model used: GPT-4o-mini via OpenAI API.

In this analysis, we use the G² (log-likelihood ratio) statistic to measure keyness, identifying terms that are significantly more frequent in one group’s posts than in others, accounting for corpus size differences.

Naturally, we estimated keyness scores for the top terms used by all 20+ nationalities in our dataset, but for brevity, this article presents examples for only four.

Weekly rents may appear when posters are looking for temporary or part-time stays. For example, staying in a city during the workweek and returning home on weekends, arranging short-term sublets (sous-locations), or needing occasional accommodation for work or tourism.

In our data, the category ‘Latin Americans’ actually combines several nationalities, such as Mexicans and Colombians. Additionally, some expat groups do use the more generic label ‘Latinos’, a broad cultural umbrella for the entire region. To keep our analysis simple, we grouped these categories together.

To guide our typology of integration dimensions, we drew loosely on the Zaragoza Declaration, which proposed a common set of EU indicators for monitoring integration outcomes in employment, education, social inclusion, and active citizenship.

While we use GDP per capita and EU membership as proxies to distinguish expat online communities, we acknowledge that these may correlate with other factors, such as users’ age, occupation, and family or migration status. Our aim is not to pin down any single group’s demographics, but to observe how different communities engage with online support spaces in distinct ways.

Here, we distinguish between the Social Belonging and Leisure and Social Activities categories. The former focuses specifically on loneliness or exclusion, for example, posters wanting to connect or reaching out to find friends. The latter, by contrast, covers posts about enjoyment, events, sightseeing and general social plans. While these categories can overlap, the Leisure dimension doesn’t necessarily imply social isolation on the part of the poster.